"If it's not broken, why fix it?"

People have a natural tendency to stick with what they know. In behavioral economics, status quo bias refers to our preference for maintaining the current state of affairs rather than embracing change. First identified by Samuelson and Zeckhauser in 1988, experiments showed that given a choice, individuals often disproportionately choose whatever option means doing nothing new. In the workplace, this bias can manifest as clinging to familiar tools and processes – even when better alternatives exist – simply because change feels uncertain. Psychologically, the bias is rooted in emotion: change involves risk, and people are uncomfortable with uncertain outcomes. As a result, decision-makers may irrationally favor the “devil they know,” allowing the comfortable status quo to win out over potentially superior innovations.

In organizations, status quo bias can be especially strong. Companies often build entire ecosystems around legacy workflows, creating a collective comfort zone. Proposals to revamp content processes or adopt new tools may trigger instinctive pushback – “we’ve always done it this way” or “if it isn’t broken, why fix it?”

The default to maintain the status quo isn’t necessarily rooted in logic, it’s often rooted in fear of the unknown.

And nowhere is this more evident than in enterprise content operations.

Why change feels risky

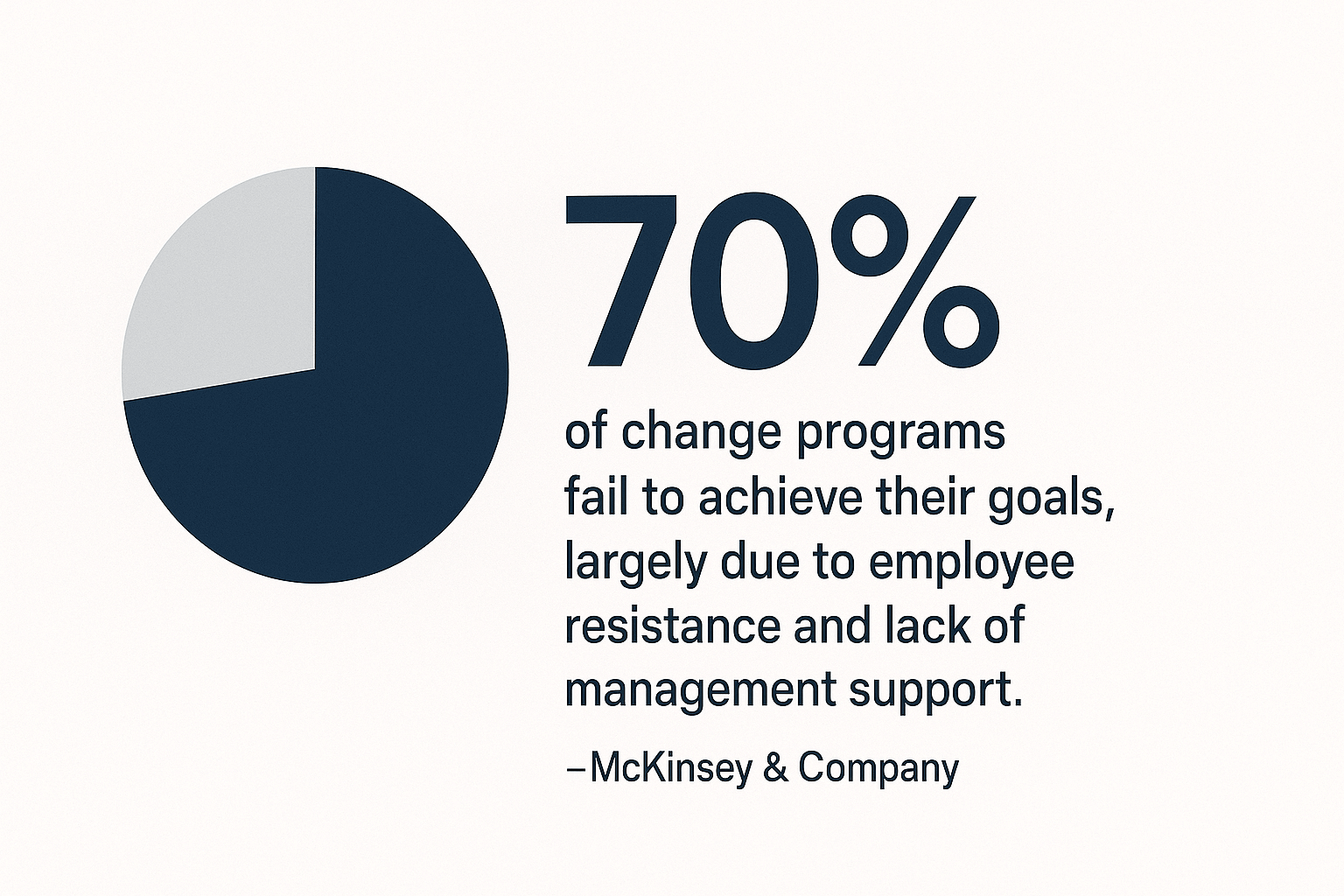

Resisting change isn’t just stubbornness – it’s human nature. Research in change management finds that employees instinctively fear disruption to their routines. People aren’t necessarily against improvement; they’re against uncertainty. Adopting a new content management system or restructuring a documentation workflow introduces uncertainty around roles, skills, and outcomes. There may be an implicit calculation going on: “Sure, the new system could be better… but it could also cause problems, or I might not adapt well.”

This is intertwined with loss aversion – we tend to weigh potential losses higher than equivalent gains. Keeping the status quo feels like a way to avoid possible losses, even if it means forgoing likely benefits.

This is compounded by the sunk cost fallacy. Organizations that have spent years building repositories of unstructured documents and creating templates for legacy tools are reluctant to “write off” that investment. The longer a flawed system has been in place, the harder it is to walk away – even if it’s clearly holding the business back.

Ironically, this can result in greater ongoing costs: license fees, workarounds, inefficiencies, and staff attrition. But these costs are often tolerated because they’re hidden – less visible than the upfront cost of transformation.

The hidden cost of doing nothing

It’s easy to assume that if documentation is still being produced – even slowly or inefficiently – the system is “working.” But that’s the trap. Standing still isn’t neutral. It’s expensive.

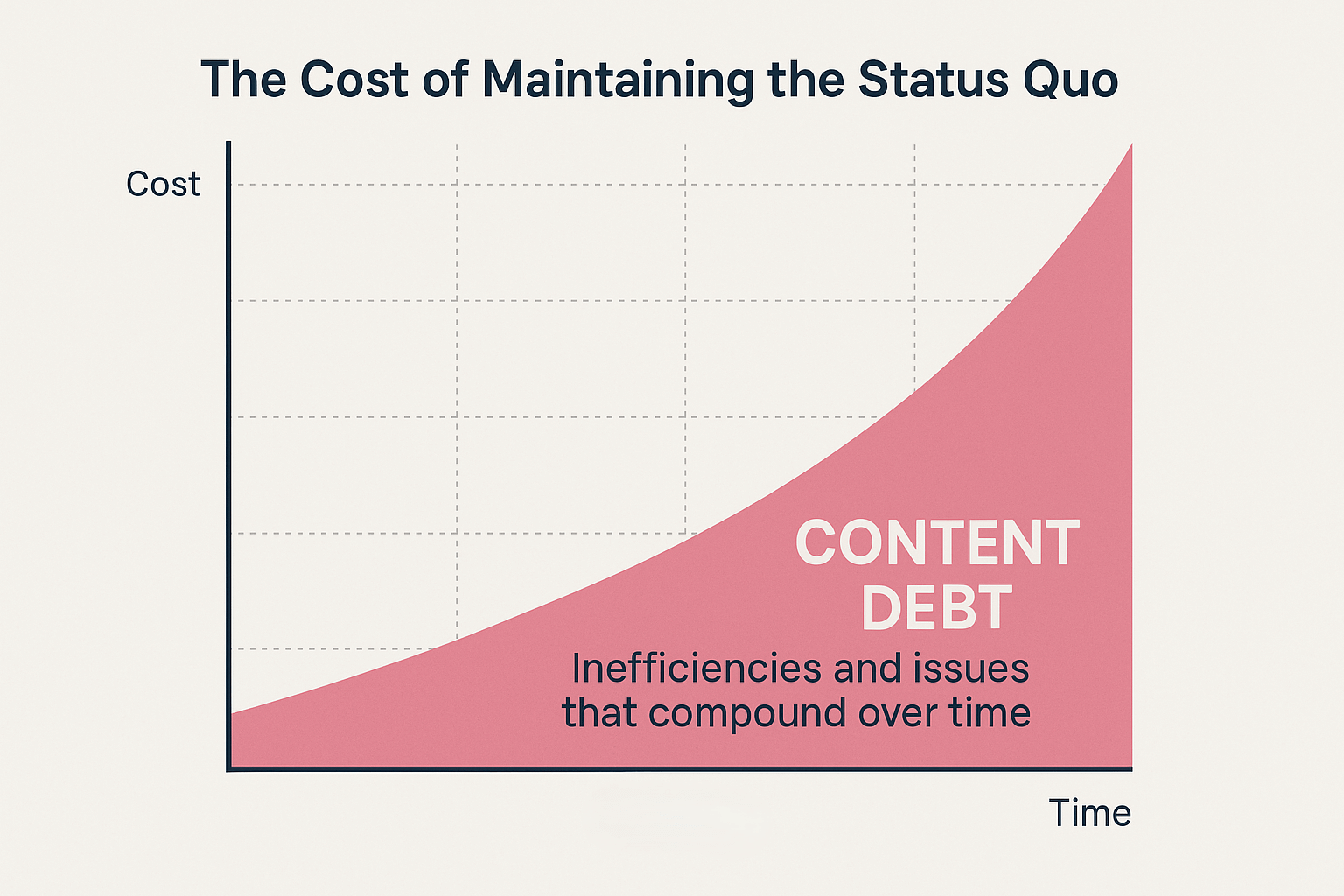

Content strategists call this content debt – the accumulation of inefficiencies and inconsistencies that result from not modernizing. Rahel Anne Bailie, Content Solutions Director at TWi, writes, “The cost of maintaining the status quo — the cost of doing nothing — accumulates ever-increasing content debt.”

This content debt surfaces in many forms: duplicate work, inconsistent quality, slow turnaround times, and even risk exposure. For example, outdated documentation workflows can lead to subpar content reaching customers (e.g. out-of-sync manuals, or inaccuracies that slip through manual processes). In the best case, this just confuses users and increases support calls; in the worst case – say in a highly regulated product – it could result in compliance violations or safety issues.

The “do nothing” approach incurs opportunity costs too: teams so busy wrestling with cumbersome templates and copy-paste updates have no bandwidth to create innovative content experiences. They miss chances to repurpose content in new channels, or to personalize and tailor information for different audiences – effectively leaving money and customer goodwill on the table.

Every hour spent hunting down the latest version of a policy document, or manually re-formatting it across print and web versions, is an hour not spent on higher-value strategy or creativity. These hidden inefficiencies add up. At scale – for organizations managing large volumes of complex, reusable, multilingual, or compliance-sensitive documentation – the “status quo” can be downright unsustainable. Such organizations often have entire departments maintaining content with antiquated methods. The processes might “work” in the narrow sense that documents eventually get produced, but often at the expense of speed, agility, and accuracy. The hidden toll is seen in slow time-to-market for information updates, poor content consistency, and burned-out employees. By contrast, organizations that buck the status quo and streamline their content operations frequently report significant efficiency gains (and relieved teams).

To put it bluntly, the biggest risk is thinking there is no risk. If competitors or upstart firms adopt smarter content operations – structured content databases, component reuse, AI-assisted workflows, real-time collaboration – they will outpace a stagnant organization. Yet status quo bias can lull companies into a false sense of security, right up until they realize they’re years behind. The hidden costs of “no change” keep compounding in the background, like interest on a debt, until eventually the pain becomes too great to ignore.

From faster horses to QWERTY

Sometimes, it’s easier to see the absurdity of status quo bias by looking at analogies from outside content operations.

Henry Ford’s apocryphal quote – “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses” – is often used to illustrate how we mistake the familiar for the optimal.

In content teams, this sounds like: “Can we just get better templates?” or “Let’s improve our PDF workflow.” But the real leap comes from challenging the model itself.

The QWERTY keyboard layout was developed in the 19th century to prevent typewriter jams. It’s not the most efficient layout – alternatives like Dvorak are objectively faster – but QWERTY persists because it’s familiar. We’ve adapted to its inefficiencies. The same is true of many legacy documentation processes: we’re so used to them, we no longer notice how poorly they serve us.

Stuck in neutral

Nowhere is this dynamic more entrenched than in industries where documentation is complex, regulatory, or product-specific – think manufacturing, aerospace, life sciences, financial services, government.

In these environments, teams often manage thousands of documents across dozens of languages, all subject to frequent updates. A change in one product detail might affect 20 manuals. A regulation might require updates across 300 procedures. A rebrand might impact thousands of headings and diagrams.

Yet many of these organisations still rely on disconnected Word files, siloed teams, and hand-stitched publishing workflows. Why? Because the alternatives – like structured content – feel like too big a leap. The irony is that it’s precisely these complex environments where structured content delivers the most value.

The longer the delay, the steeper the hill becomes. Legacy systems grow more entrenched. Workarounds multiply. Content debt becomes harder to repay. And eventually, the cost of staying the same exceeds the cost of change – but by then, the gap between the innovators and the laggards has already widened.

A different kind of case study

When Microchip, a global technology firm with over 24,000 publications considered moving to structured content, there was hesitation. The team had long used legacy tools and processes. Adopting a new system felt disruptive. Learning DITA XML felt intimidating. Change felt unnecessary.

But with the right support and a phased rollout, the shift not only succeeded – it transformed how the company thought about content altogether. Teams went from updating documents manually to managing components centrally. Reuse skyrocketed. Time to publish dropped. Reviews accelerated.

And more importantly, the mindset changed.

Rethinking what “broken” means

“If it’s not broken, why fix it?” seems sensible – until you realise the definition of “broken” is too narrow.

Is a content process “working” if it’s slow, fragile, expensive, and stressful?

Is a tool “fit for purpose” if it prevents reuse, slows localisation, and leaves teams burnt out?

Is an approach “good enough” if it holds the business back from scaling?

These are the questions content leaders must ask. Not just: Is this still functioning? But: Is this still serving us?

Breaking the bias

So how do we begin to challenge the status quo?

Psychological research suggests one powerful tactic: reframe change as enhancement. A recent study found that presenting change as an improvement to the current model – rather than a break from it – significantly increased adoption.

In practice, this might mean pilot-testing a new content tool on a small scale and highlighting how it builds on the team’s existing strengths (for example, “It’s like what we do now, but automated in the boring parts”). By lowering the perceived risk, such framing can help coax teams out of their comfort zones.

Other strategies include:

- Pilot projects: Start small. Prove the value in one area before scaling.

- Transparent metrics: Quantify the cost of the current system – hours lost, duplicate content, translation delays.

- Internal storytelling: Highlight early wins. Celebrate teams who reduce duplication or speed up publishing cycles.

- Capability building: Equip teams with the skills and support they need to thrive in a new model.

None of this is easy. But it is possible. And it’s already happening.

The first shift is mental

This blog is the first in a series about what it really takes to move from unstructured to structured content. Not just technically – but mentally, philosophically, and organisationally.

Because before any tools are adopted or workflows changed, one thing must shift first: the mindset.

Status quo bias is subtle. It whispers: “You’re fine. Don’t make it harder than it needs to be.” But the truth is, sticking with what you’ve always done is what’s making it harder than it needs to be.

In a world of accelerating change, doing nothing might be the riskiest move of all.

Curious what structured content could mean for your business?

Download our white paper to learn how others are navigating the shift – and what practical steps you can take to get started.